Retrofit or Replace: Considerations to Make When Changing Refrigerants

By KIRILL KNIAZEV

Motili

Denver CO

R-22, the refrigerant commonly known as Freon, will be — for practically all intents and purposes — banned in the U.S by 2020. With R-22 on its way out, more homeowners and contractors are seeking ways to extend the lives of their HVAC systems without using the harmful chemical. There are a variety of replacement refrigerants available, many far better for the environment.

As a result, retrofitting systems and converting them to operate with an alternative refrigerant has become an industry trend. But is converting an old system to an R-22 alternative really the best choice?

Chlorofluorocarbons

Coolants absorb heat from the environment and are vital to our modern systems of refrigeration and air conditioning. Most air-conditioning units older than a decade utilize the refrigerant R-22, commonly known by its brand name, Freon.

But R-22 was not the first refrigerant to use the trademarked brand. An earlier version was developed in 1928 as an alternative to toxic gases, like ammonia, that had previously been used as coolants. The colorless, odorless, nonflammable gas was a chlorofluorocarbon — CFC — an organic compound of carbon, fluorine, and chlorine. The chemicals were thought to be so safe that Freon was demonstrated by inhaling a lungful of the miracle gas, then blowing it out into a candle flame, which was extinguished.

Because they were nontoxic, CFCs quickly became standard in home refrigeration and air conditioning. Freon was particularly popular because its low boiling point made it a very effective refrigerant — until it was found to be unsafe and harmful to the environment.

By the mid-1970s, testing by the Environmental Protection Agency determined CFCs caused long-term damage to the ozone layer. Chlorine is rare in the Earth’s natural atmosphere, and when introduced by CFCs released into the air, it can deplete ozone. Considering CFCs have a lifetime of 20 to 100 years in the atmosphere, a single molecule can do a lot of damage. Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) — including R-22 — were developed under the theory that adding the reactive element of hydrogen would cause molecules to break down before reaching the ozone layer. In practice, however, this turned out to be largely ineffective.

As concern over ozone-depleting substances grew, an international treaty known as the Montreal Protocol was established in 1978 and ultimately signed by 197 countries — every voting member of the United Nations. The treaty vowed to gradually eliminate the production and consumption of substances that damage the ozone, including R-22.

R-22 Phaseout

In response to the Montreal Protocol, the EPA established regulations to phase out the production and import of ozone-depleting substances, including R-22 and other CFCs.

The most harmful chemicals, CFCs, halons and methyl chloroform, were among the first to be phased out, and they were originally slated to be completely banned by 2000. The EPA, however, soon accelerated this process and bumped up the date by about four years.

Other ozone-depleting substances that were a bit less harmful, such as HCFCs like R-22, were slated for the second phaseout schedule. Based on the Montreal Protocol, HCFCs must be completely eliminated by 2030, with a 99.5-percent reduction of the coolant by 2020.

As part of the phaseout in the United States, R-22 was banned from equipment manufactured on or after Jan. 1, 2010. While the chemical could still be reclaimed, recycled and reused, it was not allowed in any newly manufactured appliances or equipment. Refrigerant manufacturers were also severely limited in how much of the chemical they could produce.

Beginning in 2020, the chemical can no longer be produced or imported into the United States in any fashion. Only licensed reclaimers will be allowed to recycle or reuse the refrigerant, and only in accordance with strict guidelines. Then, in 2030, the EPA will destroy any remaining R-22.

Not only is the phaseout leaving property owners scrambling over what to do with their old HVAC systems and other appliances, but the cost of R-22 has already spiked because of the decreased supply. As a result, replacement refrigerants have been developed for machines using HCFCs as their coolants. Many contractors don’t even carry R-22 anymore.

Retrofit or Replace?

It might become nearly impossible — and expensive — to find R-22 in the next few months, but that doesn’t mean the entire country can instantly replace its HVAC systems, or that the older models won’t need to be repaired. Therefore, a variety of chlorine-free alternative refrigerants have been developed, including hydrofluorocarbon options like NU-22, 407A and MO99, to extend the life of older systems.

The availability of these alternative coolants doesn’t mean they can simply be added into a system made to use R-22. Different refrigerants function under different pressures, and systems using R-22 require a different type of lubricant. It is also important to point out that the mixing of refrigerants is illegal.

Therefore, a pre-2010 HVAC system must be converted, or retrofitted, to use alternative coolants. First, a professional must drain the R-22 from a system before replacing parts like gaskets and seals.

After evacuating the system and checking for leaks, the technician might need to add oil to the compressor before “charging” the system with alternative coolant. MO99 is a popular alternative refrigerant because it does not require an “oil change.” Its cooling capacity and energy efficiency has been shown to be fairly similar to R-22, while its lower discharge temperature can prolong the life of an older compressor.

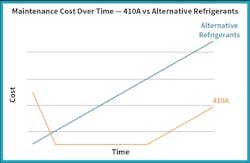

Retrofitting, however, has its drawbacks. MO99 has been known to compromise the efficiency and capacity of some existing units, while retrofitted systems often require increased maintenance.

Consider that HVAC systems retrofitted for MO99 lose 7 percent of their capacity. That doesn’t sound like much, but when a 2,400 bts machine becomes a 2,200 bts unit, the difference becomes apparent — and that’s at 90-degree temperatures. If it’s 100 degrees outside, that capacity reduction increases to 15 percent. Heating and cooling costs typically account for about 50 percent of a building’s energy usage, so that small loss of capacity will be felt when the electric bill arrives.

When the system doesn’t cool as effectively as it used to, consumers seek extra maintenance. Before you know it, the money saved by retrofitting an existing unit is quickly spent on maintenance and repairs.

At the same time, even alternative coolants like MO99 are harming the environment. Hydrofluorocarbons have been found to be a key contributor to greenhouse gases and climate change. In fact, HFCs are thousands of times more destructive to the Earth’s climate than carbon dioxide. Therefore, more than 100 countries reached an agreement to start phasing out HFCs.

An alternative to MO99 and other HFCs is a coolant known as R-410A. While at first more expensive than R-22, that is rapidly changing now that R-22 is becoming scarce. Not only is R-410A better for the environment, but equipment using the refrigerant experience fewer vibrations, which means they don’t break down as often. Some equipment can be retrofitted to use R-410A, but those conversions require major system changes and can be almost as costly as purchasing a new unit.

Today, other, even safer refrigerants are in development, and chances are R410A will be replaced at some point in the future. But as of now, every major equipment manufacturer in the United States uses R-410A in its air-conditioning systems.

There’s never been a better time to invest in new HVAC equipment. Under new tax laws, American taxpayers can save $5,000 or even more when they replace their R-22 air conditioning systems with a new model that uses R- 410A. That tax break can be used to offset the cost of replacing the system. Businesses can even deduct the full purchase price of their systems from their gross income.

Localities across the country are also supporting the change to environmentally-friendly HVAC systems. Many utility companies and co-ops are offering rebates to homeowners who upgrade their equipment. Add the tax savings and rebates to the increased efficiency of new HVAC systems, and a return on the investment becomes well within reach.