The Cost of Building Green

The article “The Cost-Effectiveness of Building ‘Green’” (October 2009) “examines available research on the cost of green buildings.” Using this research, the authors conclude there is a “misconception green buildings cost more than conventional buildings.” I argue that looking at the data more closely reveals a more nuanced pattern.

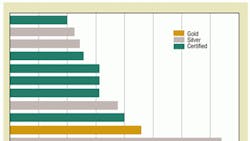

The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) study cited in the article indicates Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System cost premiums are “minimal,” but that is for buildings in excess of 250,000 sq ft. The Davis Langdon study cited in the article, meanwhile, shows large variations in cost per square foot, with little connection to certification level. The conclusion that there is “no significant difference in average costs for green buildings as compared to non-green buildings” cannot be demonstrated by the data presented. In fact, a more defensible conclusion is that LEED certification level is not a significant factor in predicting the construction cost per square foot of a building.

“The Costs and Benefits of LEED-NC in Colorado,” prepared by Enermodal Engineering Inc. for the Governor's Office of Energy Management and Conservation (www.colorado.gov/energy/images/uploads/pdfs/946f0c567450843fb8c705469e92eed7.pdf), provides construction cost per square foot, LEED cost premium per square foot, LEED certification level, and building size for 11 projects in Colorado. The data, when presented in the same format as those in the Davis Langdon study, confirm LEED level is not a predictor of project cost per square foot.

What is a powerful predictor of the additional costs associated with the construction of a LEED-certified building is building size. Data from the 11 Colorado projects show that more than 80 percent of the variability in LEED cost premium is attributable to building size.

These data correlate to the GSA report indicating a LEED cost premium of less than 1 percent for buildings larger than 250,000 sq ft. Further, as one of the authors of the Davis Langdon study explained at Greenbuild 2008 in Boston, LEED cost premiums don't scale well. Specifically, the premium for the $100 million Battery Park project in New York was $500,000. If LEED cost premiums don't scale well, a $5 million project bearing the same $500,000 premium would see a LEED premium of 10 percent.

Some assert there is a misconception about LEED costs on the part of the design and construction industry. Yet many in the design and construction industry report higher first costs for projects seeking LEED certification. There is evidence that everyone is right. Those who design and construct large projects see negligible LEED cost premiums, while those whose work primarily involves smaller buildings see significant LEED cost premiums.

Investing in sustainable design and construction is absolutely worthwhile. The long-term benefits to both the bottom line and the environment are tremendous. Yet it has been my experience and that of others that many projects have non-trivial first-cost premiums for sustainable construction; a demonstrable (and plausible) explanation for that is building size.

Mike Eissenberg, PE, LEED AP

Denver Service Center

National Park Service

Denver, Colo.

Authors' response:

If LEED is an “additive feature,” it falls into the same cost structure as all project costs when judged against project size — all fees and services cost more per square foot with smaller buildings. Our point is that there needs to be a market shift so LEED becomes standard practice, and people don't have the luxury of charging more for consulting services, trade labor, or materials just because a project is pursuing LEED certification.

With regard to Mr. Eissenberg's contention that LEED certification level is not a significant factor in predicting construction cost per square foot of a building, if that were the case, we would expect there to be more LEED Platinum buildings of all sizes and types, as it would not cost more to achieve the highest level of certification than it would the lowest.

While we agree with Mr. Eissenberg that, “Investing in sustainable design and construction is absolutely worthwhile,” we do not think building owners and developers should have to foot the bill for the learning curve of consultants and practitioners. Our conclusion, which is supported by case studies and our own project experience, is that LEED buildings do not have to cost more, regardless of square footage, when a project approach allowing better collaboration and firmer decision-making earlier in the design process is employed and LEED certification is not just an additive feature.

The bottom line is that the process by which we design, construct, and operate buildings of all sizes needs to change. While LEED certification can be achieved without an integrated design approach, with LEED an additive feature, costs are less predictable. When true collaboration between all stakeholders occurs early in the design process, the first-cost impact can be minimized or eliminated.

James D. Qualk, LEED AP, and Paul McCown, PE, CEM, LEED AP, CxA

SSRCx LLC

Nashville, Tenn.

Central Utility Plants

In his letter to the editor (October 2009) about my two-part Engineering Green Buildings column (“Rethinking Central Utility Plants,” August and September 2009), Gary Phetteplace, PhD, PE, is correct in stating I failed to mention items that run counter to my arguments against central utility plants. That was purposeful, as my goal was to get people thinking. Also, I wanted to challenge the conventional wisdom of those with vested interests; unlike them, I made sure not to state anything that could be disputed.

It is true that central plants can be and often are equipped to use more than one fuel source. Mr. Phetteplace mentions biomass, which I happen to like. Our company just completed a wood boiler project, and a colleague of mine is writing an article on the subject. However, I do not know of anyone who sees biomass as a solution to meeting our energy needs. There are some great industrial and municipal examples, but the problem is that there just aren't enough wood chips and crop residue. Mr. Phetteplace mentions using low-temperature hot-water distribution systems to reduce distribution losses, which is what I advocated in my column. The issue is that central plants historically have been used to raise heating distribution temperatures and reduce distribution-pipe sizes.

Mr. Phetteplace states the chiller advances I mentioned also are available on large-scale machines. The magnetic-bearing compressor is available in 60- to 150-ton sizes, which I do not consider large scale. Mr. Phetteplace contends the central-plant concept can deal with the “changing mix of refrigerants” better than distributed plants. Although that sounds reasonable, it is the large central chiller plants utilizing centrifugal machines that have been impacted most by the refrigerant-phaseout issue. Central chiller plants may be able to operate more efficiently than a single chiller on paper, but I was discussing the entire system, which includes distribution friction and thermal losses, as well as the effectiveness of control systems. I am sure many readers know of central chilled-water plants that have the “tail wagging the dog,” with small winter cooling loads requiring the deployment of hundreds of horsepower of central equipment.

With regard to maintenance, I have heard the argument a central plant is easier to maintain than a decentralized one, but that does not necessarily translate to reduced operating expenses. I have been around enough central plants to know many require around-the-clock supervision at significant labor expense. I did not bring that up because I like and admire plant operators, but I suspect they know they are living on borrowed time. We operate in a global economy; we have to recognize that and wise up. We need central plants, just not as many perhaps. I did mention that cogeneration and thermal-storage systems offer promise.

On a parting note, I know of a small campus in the Midwest that is extremely well-maintained, but has a steam plant requiring the operation of a 200-hp boiler 24/7/365 just to keep the distribution system hot. That is not sustainable.

Carl C. Schultz, PE, LEED AP

Advanced Engineering Consultants

Columbus, Ohio

Letters on HPAC Engineering editorial content and issues affecting the HVACR industry are welcome. Please address them to Scott Arnold, executive editor, at [email protected].

About the Author

Scott Arnold

Executive Editor

Described by a colleague as "a cyborg ... requir(ing) virtually no sleep, no time off, and bland nourishment that can be consumed while at his desk" who was sent "back from the future not to terminate anyone, but with the prime directive 'to edit dry technical copy' in order to save the world at a later date," Scott Arnold joined the editorial staff of HPAC Engineering in 1999. Prior to that, he worked as an editor for daily newspapers and a specialty-publications company. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Kent State University.