Design-Phase Commissioning: ‘Bringing the Future Into the Present’

The landscape of building engineering is constantly evolving. Design firms used to provide start-up and balancing services as part of their construction administration; now those services often are contracted out to third-party specialists. This separation increases the engineer’s level of effort in coordinating and communicating those tasks.

The following five steps can help you stay engaged during the critical aspects of construction-phase commissioning by being proactive during design-phase commissioning.

1. Document the Owner’s Project Requirements

Whatever else the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) green-building rating system has contributed to building design and construction, it certainly has lent some standard definitions to the industry. Commissioning is one of LEED’s prerequisites; every LEED project must be commissioned to some degree. Among other things, required commissioning activities include documenting the owner’s project requirements (OPR). According to the LEED Reference Guide for Green Building Design and Construction, 2009 Edition, an OPR document “should detail the functional requirements of a project and the expectations of the building’s use and operation as they relate to the systems to be commissioned.” Think of the OPR as the roadmap for the story the owner wants to tell.

At a minimum, an OPR generally requires the following information to be useful:

• Owner’s vision. Is this building going to be a beacon of the community or a no-frills workhorse?

• Project objectives. Is this building going to serve as a campus IT hub or provide parking for adjacent buildings?

• Business objectives. What are the budget, the schedule, and the funding sources?

• Sustainability objectives. How green is this building going to be?

• Delivery methodology. Will this project’s methodology be design-bid-build, general contractor/construction manager, or another method?

• Current vs. future requirements. Does this building need expandability and/or redundancy?

• Constraints. Is equipment or are vendor preferences needed to match the environment, to match other buildings, or even to adhere to a corporate “look and feel”?

Having the information to answer these questions is fundamental and critical to the design process. Identifying a design direction prior to understanding the owner’s requirements is putting the cart before the horse. Unfortunately, this cart-horse inversion is common to nearly every job; one must have an idea about what to design, but, often, that idea comes about concurrent with schematic design. The problem with this model is that the schematic design then is based on assumption, rather than documented requirements. The OPR can protect the design team by providing structure to the schematic design phase that otherwise happens by accident.

2. Develop the Commissioning Plan

The commissioning plan is a living document that outlines the commissioning process. The design team deserves to have the commissioning requirements clearly communicated to it. This plan is the best place to capture commissioning design-review schedules and responsibilities so they can be communicated and tracked. This plan also will indicate all meetings, reviews, and coordination by the engineer; these tasks should be incorporated into the engineering fee.

The commissioning plan usually is written by the commissioning authority (CxA) and supplements the OPR during the design phase by spelling out the roles and responsibilities of team members. This plan also details the requirements of commissioning during construction, and must translate those requirements into contract documents. As the old adage goes, “Failure to plan is planning to fail.” By requesting a copy of this plan during design, you thereby create the impetus for planning to begin.

3. Leverage Design Reviews

Alan Lakein, a time-management guru, said, “Planning is bringing the future into the present so that you can do something about it now.” Commissioning design reviews leverage the experience of the CxA to anticipate constructability, maintainability, or operational issues during construction. The CxA’s design review comments are evaluative from a systems perspective, made by an individual with a high degree of systems start-up and operating experience. This is not similar to a peer review, value engineering, or constructability review; the commissioning design review compares the plan to the OPR to help ensure the owner’s vision for the project is met.

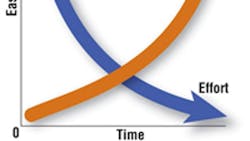

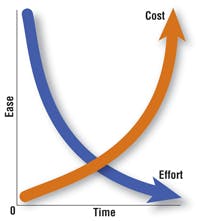

Issues identified during the design phase are much easier to resolve, and cost less to resolve, than those caught on the eve of occupancy. The engineer of record ultimately is responsible for and makes the final decision regarding project design. The CxA’s comments should reflect a consulting, not a directing, role. The CxA limits his or her comments to scope of work (commissioning facilitation vs. a peer review), and the owner arbitrates designer/CxA issues.

Commissioning design reviews could be considered a sustainability topic, as a review could extend beyond mechanical systems to encompass building envelope, lighting, environmental aesthetic elements, wall systems, and unique and novel ideas. Finally, issues addressed during design reduce the number of requests for information and change orders during construction, which improves cost performance, schedule protection, and designer image and reputation.

4. Define Construction and Post-Occupancy Commissioning

Requirements

In this step, the CxA moves from observer/reviewer to a creative role. Principally captured in commissioning specification sections, the contractor’s responsibilities for commissioning-program support should include the testing and documentation requirements for the systems to be commissioned. These could include specific training objectives, spare parts, global set point adjustments, equipment or building scheduling, or assistance supporting the owner’s computerized maintenance system. This specification detail often is generated by editing the design engineer’s specification sections. As the engineer of record, you should be aware of these edits and any additional specification sections the CxA provides, as these often are combined with other mechanical or electrical technical sections and all too often not stamped and sealed separately.

Legality aside, you should review the CxA’s contribution for coordination and redundancy. If, for instance, the CxA is planning to log trend data with a remote computer that won’t be connected to the site before the trend period, you could help flag this coordination challenge before it becomes an issue. Here you’re being a team player and improving the overall project outcome.

5. Start Early

Commissioning during the design (and predesign) phase of a project should not happen in a vacuum. The project engineer will be affected by the CxA’s effort and, therefore, should have a say in how the commissioning program is conducted. The CxA can be a powerful ally working toward making installed systems function as intended. As a result, the project engineer should get engaged in the commissioning process as early as possible.

The framework of the engineer’s control and influence during construction is laid out during the design. Commissioning is a quality-assurance process that begins during design and extends through construction. Engineers should work through the commissioning framework with the CxA to help realize the owner’s vision for a project.

Jeff L. Yirak, PE, LEED AP BD+C, O+M, is associate, commissioning, for Wood Harbinger, and treasurer of the Northwest Chapter of the Building Commissioning Association. He can be reached at 425-628-6041 or by e-mail at [email protected].