In November 2010, I attended the U.S. Green Building Council’s Greenbuild Conference and Expo in Chicago. One of the presentations I heard there was on the topic of Integrated Project Delivery (IPD). For those not familiar with IPD, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) defines IPD as a collaborative project delivery approach that utilizes the talents and insights of all project participants through all phases of design and construction.

So what does that really mean? More than any of the other so-called collaborative project delivery methods – construction manager at-risk, fixed-price design-build, or progressive design-build – IPD brings the project delivery process back to its grass roots… owners partnering with designers and builders to construct facilities guaranteed to meet the owner’s needs, on-time, on-budget, and built properly.

I was so excited about what I heard that, when I returned home to South Florida, I persuaded a number of my colleagues – representing architects, civil engineers, structural engineers, MEP engineers, interior designers, landscape architects, general contractors, mechanical contractors, electrical contractors, and commissioning authorities – to form Team IPD, “Florida’s Integrated Project Delivery Team.”

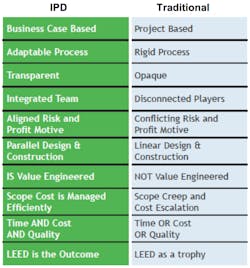

When compared to both traditional design-bid-build and design-build models, IPD offered some significant advantages:

That’s the good news. The bad news?

We were a little ahead of our time, and we did not get enough traction to keep the venture together. There were several factors that contributed to Team IPD’s lack of success. Florida has rarely been an early adopter of those types of innovations, and state and local procurement regulations made contracting for public projects using IPD all but impossible. We even tried to convince some energy service companies (ESCOs) to use IPD to execute their energy savings performance contracts. In Florida, ESCOs are qualified under a state term contract, and any governmental entity within the state can contract with a listed ESCO using a streamlined procurement process.

Unfortunately, the ones we contacted had no interest trying to integrate IPD into their system for retrofitting existing buildings, and ESCOs are not generally involved in new construction. Although the private sector should have been receptive to IPD, because it was new, and owners were not familiar with it, they were – not surprisingly – resistant to being “guinea pigs”.

Growing acceptance

Today, IPD is better accepted by many private owners, and the use of IPD in the private sector appears to be steadily increasing. Here in Florida, I am aware of only one significant IPD project: Universal Health Services’ Wekiva Springs Center in Jacksonville. It used what was characterized as a small ($10-20-million budget) renovation/new addition project to add approximately 60 beds to an existing healthcare facility. The project, completed in 2005, utilized a modified version of a standard IPD agreement which was adapted to be multiparty, with the financial structure focused on target costs and at-risk profits. Lean processes were also a key part of the design and construction activities.

Unfortunately, most public procurement processes still require a very prescriptive process in order to stand the scrutiny of taxpayer watchdogs, although there are some notable exceptions. Colorado, for example, was an early adopter, introducing the Integrated Delivery Method for Public Project Act in 2007. This legislation allowed state agencies to enter into an IPD contract with a single participating entity for the design, construction, alteration, operation, repair, improvement, demolition, maintenance, or financing, or any combination of these services, for a public project, so long as the agency determined that IPD represented a time- or cost-saving alternative to traditional contracting.

Widespread adoption of IPD, in both the private and public sectors, may eventually help fix the U.S. construction industry, which many believe to be broken. In the meantime, for those jurisdictions that do not permit IPD for public projects, progressive design-build may be the best option. This is especially true for more complex projects, since the owner directly participates in design decisions.

The author is a principal at Sustainable Performance Solutions LLC, a south Florida-based engineering firm focusing on energy and sustainability. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Larry Clark

A member of HPAC Engineering’s Editorial Advisory Board, Lawrence (Larry) Clark, QCxP, GGP, LEED AP+, is principal of Sustainable Performance Solutions LLC, a South Florida-based engineering firm focused on energy and sustainability consulting. He has more than two dozen published articles on HVAC- and energy-related topics to his credit and frequently lectures on green-building best practices, central-energy-plant optimization, and demand-controlled ventilation.