Don't Let Record-High CO2 Levels Cloud Our Thinking

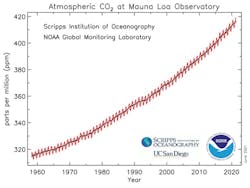

In May 2018, I wrote about the Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO) in Hawaii that, after taking daily measurements of atmospheric CO2 since 1958, recorded its first-ever reading in excess of 410 parts per million (ppm).

The significance of that, in addition to its impact on climate change, was its effect on building ventilation. If we assumed a CO2 differential of approximately 617 ppm above ambient outside air conditions at ASHRAE 62.1 ventilation rates, then an outside air concentration of 410 ppm would result in an indoor air CO2 level of 1,027 ppm. It’s been well-established that CO2 levels as low as 1,000 ppm can cause drowsiness, and can impair concentration and logical thought processes.

Now, exactly three years later, measurements taken at the observatory are even higher. At 419 ppm, this is the highest monthly average of atmospheric CO2 in more than four million years.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), that operates MLO, the last time CO2 levels were that high was during the Pliocene Epoch, when average sea levels were 78 feet higher than now, and the planet was 7 deg. F. warmer. It’s even possible that today’s Arctic tundra was the site of large forests.

Since 1958, the atmospheric CO2 recorded at MLO has increased 133 percent, an increase of approximately 1.65 ppm per year, and the curve does not appear to be flattening.

In fact, during the three-year period from 2017 to 2019, atmospheric CO2 increased by 1.76 ppm per year (403.27 ppm to 408.55 ppm). Last year’s drop in daily CO2 emissions due to the pandemic (by early April 2020, daily global CO2 emissions had already dropped by 17 percent over 2019, and here in the U.S. where we have higher vehicle usage, reductions as large as 33 percent month-over-month were reported) may explain why this year’s level was only 1 ppm higher.

If you believe the science, as do I, we know that most of the increase in greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) over the past 150 years have been due to human activities, the majority of that from burning fossil fuels for electricity, heat, and transportation. Clearly, finding renewable energy alternatives must continue to be a priority for our scientists and engineers.

Once the technologies are in place, the politicians and policymakers can then do their part.

##########

- Listen to Larry Clark in the first episode of our podcast series, HPAC On the Air.

##########

A regular contributor to HPAC Engineering and a member of its editorial advisory board since 2012, Clark, LEED AP, O+M, is a principal at Sustainable Performance Solutions LLC, a south Florida-based engineering firm focusing on energy and sustainability. Email him at [email protected].

About the Author

Larry Clark

A member of HPAC Engineering’s Editorial Advisory Board, Lawrence (Larry) Clark, QCxP, GGP, LEED AP+, is principal of Sustainable Performance Solutions LLC, a South Florida-based engineering firm focused on energy and sustainability consulting. He has more than two dozen published articles on HVAC- and energy-related topics to his credit and frequently lectures on green-building best practices, central-energy-plant optimization, and demand-controlled ventilation.