Since beginning Clark’s Remarks in 2013, innovative air conditioning solutions have been a recurring topic. Some, like solar direct-expansion air conditioning, fell short of expectations. Others, like thermo-acoustic AC, are still hopefully being developed. Many of the posts addressed control technologies and, encouragingly, the majority of them have shown success.

Coming off of this year’s summer swelter, air conditioning is on nearly everyone’s mind, especially when it stops working.

The old adage that you “can’t live with ‘em and can’t live without ‘em” seems very appropriate. With this year's dangerously high outside temperatures, functioning AC is critical not just to comfort, but for health. Keeping the AC on during these heat events is priority one (ask the California power grid managers).

Unfortunately, conventional AC is bad for the environment. The damage to the climate from AC is three-fold: excessive energy consumption, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from refrigerants, and the heat rejected from interior structures to the outside environment.

Although the most climate-damaging refrigerants have continued to be phased down or out, the replacements have still left a lot to be desired. Here’s a quick review:

We started with the CFCs like R-11 and R-12 that had very high ozone-depletion potential (ODP) and global-warming potential (GWP), and they were phased out between 1987 and 1996 under the terms of the Montreal Protocol. They were generally replaced by hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) refrigerants such as R-22, which had medium ODP and GWP. Next came, the hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants, such as R-134a and R-410a, with zero ODP and medium GWP, and were scheduled to be phased out by the Kyoto Protocol. The widely accepted replacements for HFCs are low ODP A2L refrigerants. The bipartisan American Innovation and Manufacturing Act of 2020, and the corresponding EPA rules, are now expected to reduce the supply of HFCs by 40% in 2024.

Of course, the energy consumed by AC also contributes to the global climate crisis.

Even with the efficiency improvements seen over the past four decades in technologies like variable refrigerant flow (VRF), AC is still an energy hog. That’s why the work being done at Harvard University (the Wyss Institute, Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, and the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities) on their coldSNAP system is both timely and encouraging. SNAP stands for superhydrophobic nano-architecture process, a process which uses a water-repelling nano coating inspired by the water repellency of duck feathers. The project team is led by researchers Jonathan Grinham and Jack Alvarenga (pictured above, from left to right).

Their coldSNAP system is essentially an evaporative cooler (EC) without the limitations of working only in dry climates. Because ECs (colloquially known as swamp coolers) flow hot, dry air over water saturated pads and allow natural evaporation to cool the air stream, they are only effective in low-humidity locales. Since there are no high-energy consuming compressors or refrigerants, they are environmentally friendly. In hot-humid climates, like coastal South Florida where I live, ECs won’t work, because they actually add humidity to the space to be cooled. The coldSNAP system, according to the researchers, uses its unique nano coating to effectively isolate the water vapor from the air that is released into the interior space, preventing it from contributing to the indoor humidity while still cooling the air. Just as in conventional ECs, the coldSNAP has no compressor or refrigerants, so it’s environmentally friendly.

- Watch the explanatory video here.

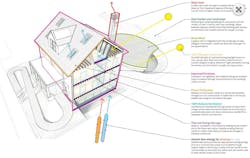

With the Boston area’s recent hot, humid days, the researchers had an ideal location to test the coldSNAP… their experimental HouseZero, the retrofitted Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities headquarters, a pre-1940s building in Cambridge. If it can perform at commercial scale, its environmental friendliness, along with its expected low cost to manufacture and operate, might allow it to be used with a less-efficient dehumidifier to replace conventional vapor compression air conditioning.

Stay tuned...

A regular contributor to HPAC Engineering and a member of its editorial advisory board, the author is a principal at Sustainable Performance Solutions LLC, a south Florida-based engineering firm focusing on energy and sustainability. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Larry Clark

A member of HPAC Engineering’s Editorial Advisory Board, Lawrence (Larry) Clark, QCxP, GGP, LEED AP+, is principal of Sustainable Performance Solutions LLC, a South Florida-based engineering firm focused on energy and sustainability consulting. He has more than two dozen published articles on HVAC- and energy-related topics to his credit and frequently lectures on green-building best practices, central-energy-plant optimization, and demand-controlled ventilation.